Most real estate investors watch interest rates like hawks. The smart ones follow the debt cycle. A few even track monetary policy.

But almost nobody watches the insurance cycle. And right now, it's quietly destroying deals from Miami to Malibu.

And I don’t mean - watching their insurance premium rise. I mean, watching and understanding the cyclical nature of insurance itself.

I've been thinking about this a lot lately. We're six years into what might be the longest insurance hard market in modern history. Premiums are up 200-300% in some markets. Carriers are fleeing entire states. And if you're trying to close a deal in Florida or California right now, you know exactly what I'm talking about. But it’s not just the usual markets - something is going on.

This isn't some temporary blip. It's a structural shift that's repricing risk across the entire real estate ecosystem.

Understanding the long-cycle of insurance is critical for any real estate investor, because it has a massive impact on our business, on profitability, and on the future potential of your portfolio and investments.

What Is the Insurance Cycle?

Think of insurance markets like a pendulum swinging between feast and famine.

In soft markets, capital flows freely. Premiums drop. Underwriters get loose with their checkbooks. Combined ratios (claims plus expenses divided by premiums) hover around 95-105%, and insurers lean heavily on investment income to stay profitable.

In hard markets, catastrophe wipes out capital. Premiums spike 15-35% in normal cycles—or 50-300% after severe events. Coverage gets stripped down to bare bones. Combined ratios can hit 140%+, forcing insurers to retreat from entire markets.

Historically, these cycles lasted 3-4 years. You could ride them out. But something changed.

The soft market from 2009-2017 lasted nearly a decade, the longest in modern history. The current hard market started in 2018 and shows zero signs of easing. As of mid-2025, commercial property rates are still climbing, reinsurance is scarce, and insurers are cutting exposures.

Risk Is as Old as Civilization

The instinct to share risk goes back to the beginning of recorded history.

Babylonian merchants used "bottomry contracts" around 3000 BCE—loans secured by cargo that were forgiven if the ship sank. The Code of Hammurabi codified these arrangements. Roman burial societies pooled dues to cover funeral costs.

By the Italian Renaissance, Genoese traders had created standalone marine insurance. A 1347 policy—the oldest surviving example—formally separated credit from risk transfer.

Edward Lloyd's coffeehouse in 17th-century London became the hub of marine underwriting. Professional underwriters formalized it by 1769. Parliament codified it by 1871.

From ancient Babylon to modern reinsurers, the story has always been the same: civilization only functions when someone is willing to carry the tail risk. For a price.

When Insurance Breaks, Everything Breaks

Here's what most people miss: insurance is the gatekeeper of real estate.

When coverage is cheap and readily available, projects pencil out. When it's expensive, restrictive, or unavailable, projects die, valuations crater, and risk gets repriced.

And importantly, existing owners facing suddenly massive premium increases may be forced to sell at prices they don’t like, simply because of the premium increases.

We recently underwrote a property where the owner had been paying $40,000 per year for insurance. When the insurer backed out of the market writ large, the premiums rose to ~$150,000 per year! I’ve seen deals where the current premiums today are over $200,000 (on comparable-sized assets).

According to the Insurance Information Institute, over 30 carriers have fled Florida since 2020. California's FAIR Plan—the state's insurer of last resort—now covers over $450 billion in property exposure, up 61% since 2020.

In both states, deals are falling through because buyers can't secure insurable interest. Some homeowners are paying $ 10,000 or more annually for coverage—if they can find it at all.

I've seen multifamily operators in Florida report 200%+ premium increases over two years. In California's wildfire zones, owners are being forced into surplus lines markets with stripped coverage and zero liability protection.

California is also an interesting case. There’s an argument to be made that the California Government is artificially suppressing insurance premiums, which is having a chilling effect on the insurance market and causing insurers to leave the state. Think about the downstream impact here.

Why suppress premiums?

Because premiums would be much higher. But why does that matter? Well, if your homeowners' premiums increased by 4x, it would make your home borderline unaffordable for many Californians. This would cause home sales. New buyers would reprice the home based on the new insurance premium, resulting in significant losses in home value.

That’s tough for owners. That’s really bad for California, because California resets the property tax basis on sale. But this reality may be coming, with almost all major insurers simply gone from California.

For small to mid-sized operators—the backbone of the rental market—this isn't sustainable. They're pulling out of markets, raising rents aggressively, cutting maintenance, or repricing everything downward.

Insurance is doing what rising rates did in 2022-23: quietly destroying asset values. Until a deal doesn't close. Or a fire reveals the coverage gap.

Consider that even a $1,000 increase in premium equates to an $18,181 loss in value (based on a 5.5% capitalization rate). So a doubling of premiums for most properties is a massive value loss.

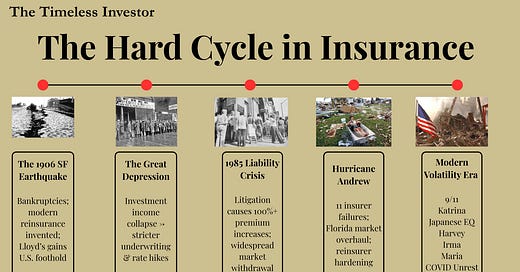

The Gory History of Premium Spike Events

Insurance premiums have always spiked after catastrophe. But some moments stand out for fundamentally shifting risk appetite:

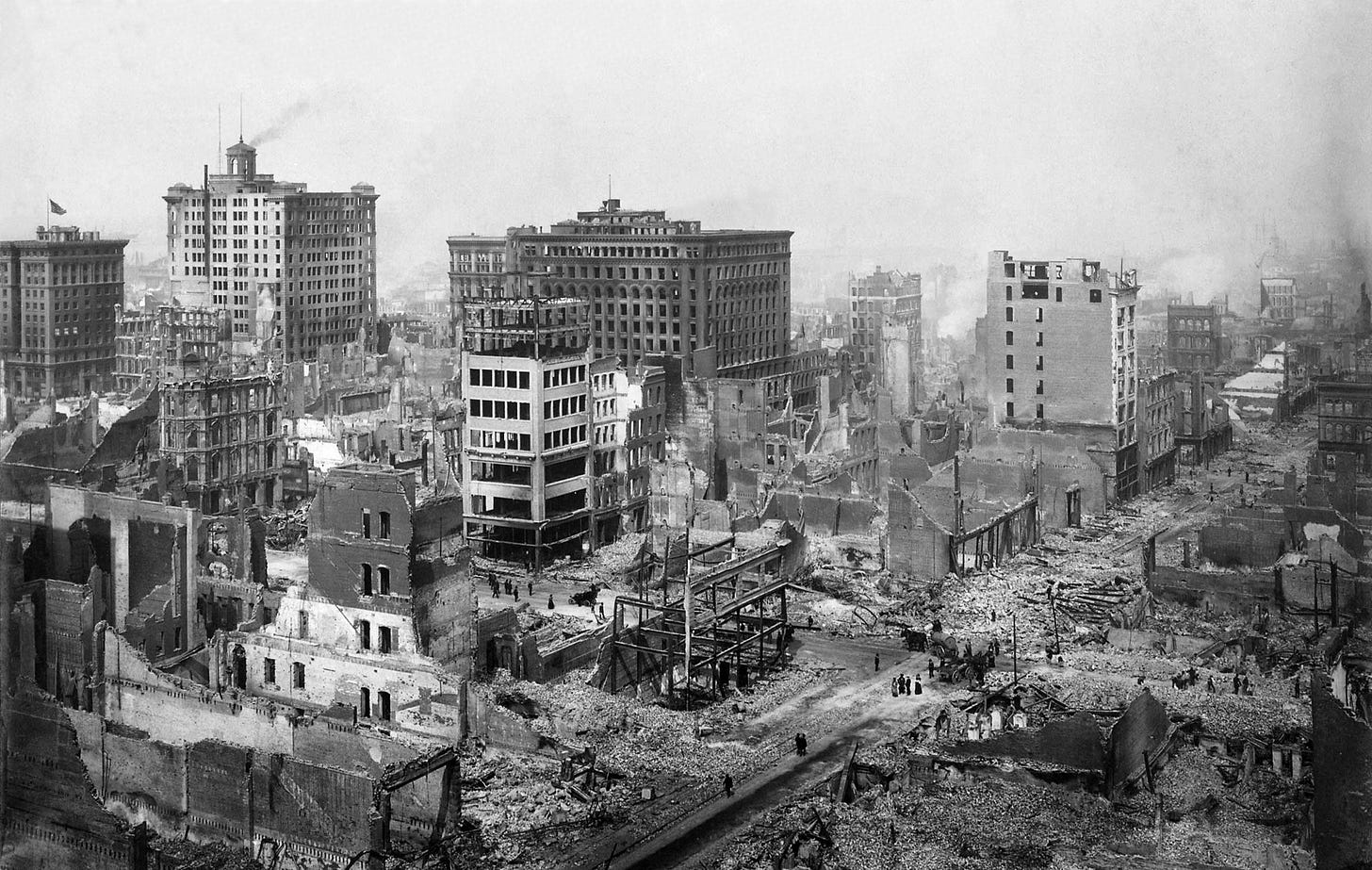

1906 San Francisco Earthquake: Losses exceeded the previous 47 years of combined U.S. insurance industry profits. Premiums surged nationwide. Lloyd's paid claims in full, establishing its global reputation.

Post-9/11: Terrorism insurance, once bundled for free, became a $5-10 billion annual line overnight. Aviation insurance rose 500%.

Hurricane Katrina (2005): Coastal rates jumped 40-100%. Reinsurance became scarce. Global pricing tightened.

Florida 2022-2024: Some homeowner premiums jumped from $2,500 to over $10,000. More than 30 carriers exited. Citizens, the state insurer, ballooned to over 1.3 million policies.

Premium volatility isn’t new. However, today, the spikes are faster, sharper, and more geographically widespread — driven not only by catastrophe, but also by litigation, inflation, and advances in modeling.

Importantly, the repeated battering of the Southeast — from Andrew to Katrina to Ian — is now having ripple effects on the entire U.S. insurance market. Because reinsurance is a global industry, capital losses in one region necessitate pricing adjustments everywhere.

When reinsurers take repeated hits, they don’t just raise rates in Florida — they raise them in Colorado, Oregon, Illinois. No property is truly isolated in a global risk pool. This is the new cascade effect of climate and capital stress.

For instance, SwissRE estimates that global insurance premiums would rise around 4.3% in 2025, driven by catastrophic climate change-related losses. In other words - a property owner in Idaho might be paying a higher premium because of hurricane losses in Florida.1

Follow the Combined Ratio

One of the better indicators of where we are in the cycle is the combined ratio—claims and expenses divided by premium income.

Under 100% means underwriting profits. Over 100% means underwriting losses, with insurers relying on investments to offset the gap.

From 1979 through 2003, the U.S. property and casualty industry failed to post a single year of underwriting profit. Not one.

In 2022, the industry posted a combined ratio of 105.8%—a $20 billion underwriting loss. Forecasts for 2025 estimate around 98.5%, indicating ongoing strain despite rising premiums.

But here's the catch: combined ratio data reflects the performance of primary insurers, not reinsurers. And over the past decade, reinsurers have been absorbing an outsized share of the pain.

This creates a false sense of security. Between 2017 and 2021, combined ratios appeared stable — hovering near or just below 100%. But those numbers masked a deeper problem: reinsurers were bleeding. By 2022, with repeated $100+ billion catastrophe years and eroded capital bases, reinsurers raised prices, tightened terms, and pulled back from markets altogether.

That pressure cascaded down to primary insurers in 2022 and 2023, and now to property owners and real estate investors.

So yes, combined ratio is useful — but don’t let the 98.5% headline lull you into thinking the system is stable. The real losses were just being absorbed elsewhere, until the dam broke.

A New Paradigm?

The current hard market is already six years long and counting. That's unusual. But several structural factors suggest we may be entering a new era of permanently tighter insurance conditions:

Climate change is increasing the frequency and severity of catastrophes. AI-driven underwriting is surfacing previously unpriced risks. Litigation costs are ballooning, especially in Florida and California. Reinsurers are pulling back from U.S. property risk, reducing capacity.

Together, these forces may mean the old 3-4 year cycles are dead. Instead, we may face a multi-decade realignment of how risk is priced and transferred.

And what does this - a longer, harder cycle - mean for real estate investors?

Here’s an eye opening chart from researchgate. You’d be hard pressed, looking at this, to argue that weather related losses have not increased over time. And so -potentially - fundamentally changed the industry and premiums.

The Multifamily Reality

In multifamily, insurance is now the fastest-growing expense line. According to Marcus & Millichap, average per-unit premiums rose 33% year-over-year in Q2 2023.

Many operators are now:

Pulling out of certain markets entirely

Raising rents aggressively to offset expenses

Cutting back on maintenance and upgrades

Repricing risk into acquisition models (lowering offers accordingly)

This hits small to mid-sized owners the hardest. They don't have the scale to self-insure or the leverage to negotiate better terms.

The Investor Takeaway

If you own, operate, or underwrite real estate—especially in climate-exposed markets—you must start treating insurance not as a line item, but as a strategic input to asset selection and valuation.

This isn't temporary. It's a regime change.

The winners won't just be the best operators or capital allocators. They'll be the ones who understand how risk moves through the system and position accordingly.

Because when insurance breaks, everything downstream breaks with it.

If you enjoy this content, check out The Timeless Investor Show for deep dives on finance, history, and real estate.

https://www.swissre.com/dam/jcr%3Adbe1695d-7cf9-4a14-bc37-52465fe4789a/sri-sigma-global-economic-insurance-market-outlook-2025-2026.pdf

Fantastic article