It seems, based on a study of history, that the fate of Empires is much like that of wealthy families. The first generation are the builders - the ones who struck gold, who built something out of rugged nothingness. The second generation faithfully maintains the vision. However, the third generation is where the troubles arise.

In Empire and Nations, the key thematic point, in my view, is that societies initially build productive industrial bases. They grow, they expand, they conquer. But eventually, their power - their hegemony - leads to the pursuit of profit. Specifically, financial profit.

You see - the issue becomes simple - it becomes far more lucrative and valuable to make money on money than to create something new. And at that point, nations begin to hollow out. Their productive capacity fades.

And it can work - for a long time. However, the lessons of history remain true today - we must be mindful of these things. And what they mean for modern-day investors with heavy allocations to the United States.

So, with that in mind - let’s focus on the Empire on which the sun never set.

In 1815, the fate of Europe was being decided on the fields of Waterloo. But the real power shift didn’t happen with muskets or cavalry charges.

It happened in the bond market.

That year, as Wellington fought Napoleon, Nathan Rothschild used one of the most sophisticated intelligence networks in Europe to get the outcome of the battle before anyone else. He front-ran the British government's own information. And with it, he front-ran the market.

He didn’t just make a fortune. He signaled the beginning of a new era: one where information, speed, and capital markets could rival armies. I cover this story in detail in the Timeless Investor Show here.

Britain may have won at Waterloo, and secured their way of life. But in many ways, the financialization of the British Empire started then.

The Empire That Conquered the World with Credit

In the 19th century, Britain built a global empire. But unlike Rome, it didn’t rely purely on military conquest. It did something more subtle. More scalable.

It created a financial operating system.

The City of London became the center of global bond markets. British naval power enforced security, but British debt markets enabled expansion.

They lent to colonies. They backed railroad development. They funded wars. And they exported British financial norms everywhere they went: contract law, central banking, private capital.

In doing so, they embedded their empire in balance sheets, not just maps.

It worked. For over a century, Britain turned debt into dominance.

In many ways - this is a reflection of modern trends. Making money on money becomes the game. And for awhile - a long time - it is extremely lucrative.

A mentor and good friend of mine once said that the best and brightest in the United States tend to go into investment banking. But - he pointed out - investment bankers don’t produce anything. They grease the skids of transactions. They make huge profits.

But what value have they produced?

The Hollowing Out Begins

But as the empire matured, something started to shift.

By the early 20th century, a growing share of the British economy had moved away from manufacturing, agriculture, and productive trade - and into finance.

Making money on money became more profitable than building, producing, or innovating.

By the mid-20th century, services dominated Britain’s GDP - with financial services growing rapidly in influence. Meanwhile, industrial capacity declined. Manufacturing jobs shrank. Domestic innovation slowed. Britain became a global financial hub - but at the cost of real economic depth.

This transition made the economy fragile. Financial services are high-margin, but also high-volatility. And when global capital flows shifted, the British economy had little to fall back on.

The City of London remained powerful. But the country beneath it became hollow.

And Then the Wars Came

The cracks became undeniable during the world wars.

In World War I, Britain entered as the global financial hegemon - but quickly found itself stretched. Financing the war effort required massive borrowing, much of it from the United States. Its industrial base, already diminished, couldn’t keep pace with the demands of total war.

By World War II, the situation was worse. Britain was isolated, its overseas empire increasingly under siege. German U-boats severed supply lines. Colonies were destabilized. And at home, the economy lacked the industrial muscle it once had.

Britain had become reliant on its empire - and on its financial system - to project power. But when the empire was cut off and capital couldn’t win battles, it had no foundation to stand on.

America stepped in. First with Lend-Lease. Then with soldiers and unlimited quantities of war materials, backed by its massive industrial base. Then, ultimately, with the Bretton Woods system that replaced Britain with the U.S. at the center of global finance.

Britain survived the wars. But the empire didn’t. Because empires built on capital alone can’t stand when the storm hits.

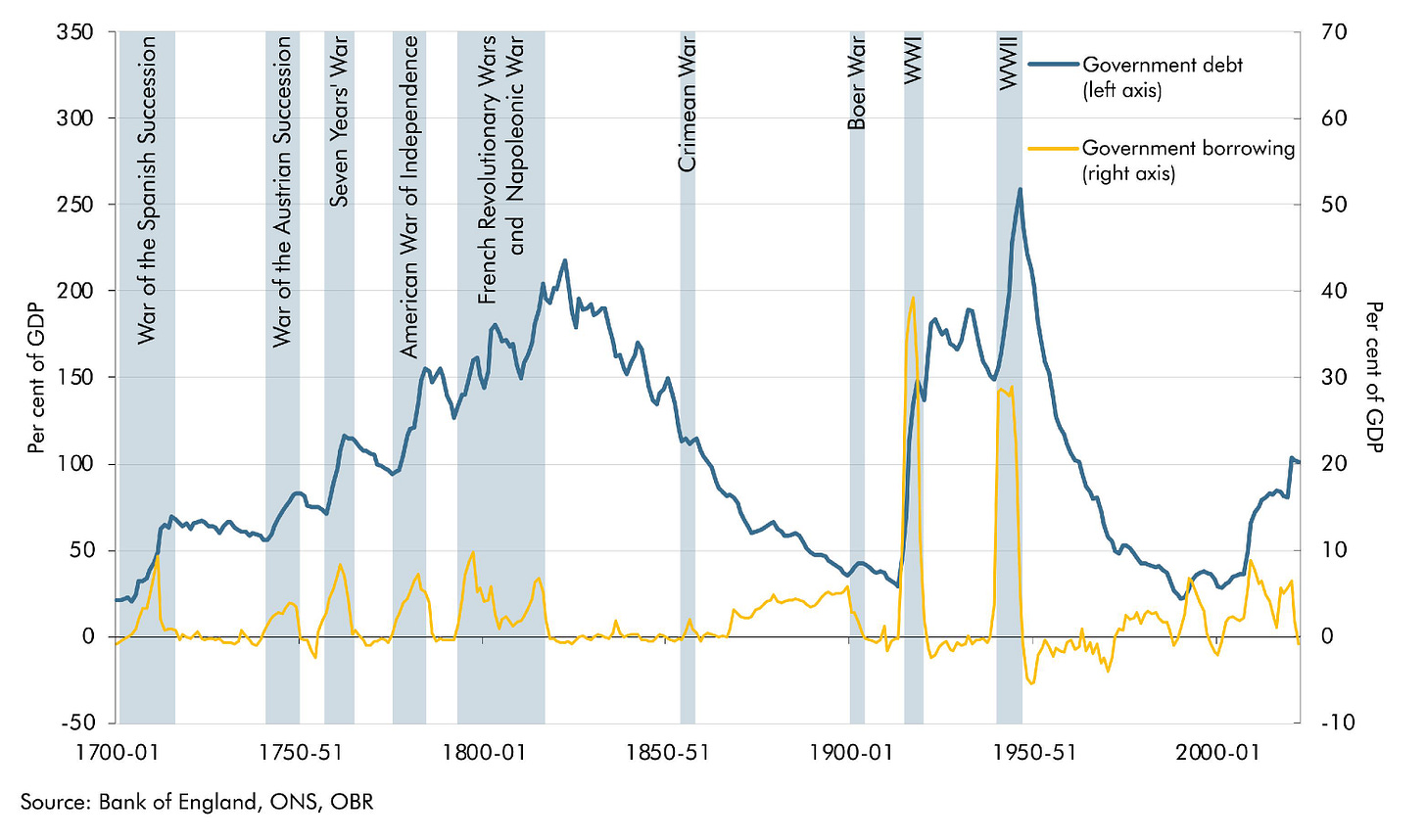

By the way - fascinating side note. Take a look at the chart below and the Debt to GDP - you’ll note the trajectory and rise of government debt looks an awful lot like the United States. I’ll also note that during the period of the prevailing Gold Standard, as discussed in this piece - debt declined precipitously.

This, to me at least, points directly to the value of the gold standard. You’ll note the rapid decline of debt in the period between 1850 and WW1, which is a direct function of having a hard currency.

America Took Notes

Fast forward to the 20th century. The British Empire began to fade.

But the playbook didn’t disappear. It migrated.

After WWII, the U.S. picked up where Britain left off. It rebuilt Europe with loans. Backstopped global trade with dollars. And grew a domestic capital market so big, so liquid, that the dollar became inescapable.

Today, the U.S. bond market is our empire. $30+ trillion deep. Backed by military, but governed by debt issuance.

We don’t export tanks anymore. We export Treasurys.

And the rest of the world buys them.

And thanks to that immense financial strength, the United States is the pre-eminent power in the entire world. But it has also led, inevitably, to excess - just like it did for Britannia.

Are We Hollowing Out Too?

In 2024, financial services account for over 20% of U.S. GDP. Another 10% is from real estate transactions. And a staggering portion of our tech economy is oriented not around producing goods - but monetizing data, ad spend, and speculative capital.

Meanwhile, U.S. manufacturing as a share of GDP has dropped below 11%. In the 1950s, it was over 25%.

We're seeing the same shift Britain went through: from production to intermediation. From building value to extracting it. From making things to managing flows.

The problem? Financialization is lucrative in the short term. But it doesn’t anchor a society. You can't eat derivatives. You can't export TikTok.

Just like Britain, we’re turning the financial engine into the entire economy. And just like Britain, we may find that when the tide turns - there’s less under the surface than we thought.

The Danger of Mistaking Leverage for Leadership

The British Empire didn’t collapse overnight. It eroded, slowly, as debt obligations rose and productive output stagnated.

The financial system kept growing, even as the underlying power that supported it shrank.

Sound familiar?

Today, America runs fiscal deficits every year. Debt-to-GDP is near 120%. Entitlement spending is ballooning. And every crisis is met with the same tool: more liquidity.

We’ve turned the financial engine into the entire economy.

But engines burn out.

Britain’s did. And when it did, the world moved on.

What This Means for Investors

I am not predicting imminent collapse. The United States is a tremendously strong country. We have an enormous productive base and a workforce envied worldwide.

But I am suggesting this:

The U.S. is following the same script Britain wrote 200 years ago.

And if that’s true, then the most critical investing question of the next 10 years isn’t just what assets you own. It’s whether those assets will hold value when empire inevitably shifts.

In the 20th century, the best trades were long the dollar, long U.S. growth, long American credit.

In the 21st?

It might be long scarcity. Long real assets. Long optionality. And long whoever writes the next chapter of global finance.

We do have some evidence of what happened to land-holdings in the UK with the fall of Empire. Productive land - yielding land - performed well. Many aristocratic estates preserved value. London - obviously - did extremely well. As one of the finance hubs worldwide, capital continues to flow into the City of London.

My take here is that productive, yielding, scarce real estate in major cities will continue to be powerful hedges against any shifts in Empire. Real assets hold value well in currency depreciation scenarios, which is absolutely the paradigm we are living in right now.

We learned how to win from the British.

But we might be borrowing their ending too.